Pre-colonial Roots and Indigenous Presence

The area around Falls Church is believed to have been inhabited by people for approximately 15,000 years, dating back to the Paleo-Indian period1. In 1985, during construction of the Marriott Hotel at Fairview Park near Routes 50 and 495, Fairfax County archaeologists recovered Native American artifacts dating between A.D. 200 and 1500. Artifacts from another site located on present-day Crossman Farm provide evidence for a permanent Native American settlement2.

By the time of English arrival in the early 1600s, the local inhabitants were Algonquian-speaking tribes. The primary indigenous group inhabiting the immediate Falls Church vicinity was the Dogue (also spelled Doeg or Taux), who lived along the Potomac, farming corn, fishing, and hunting in the area3. Captain John Smith's 1608 exploration up the Potomac River documented "11 different native groups" between the Chesapeake Bay and Little Falls of the Potomac40.

The Powhatan Confederacy, led by the paramount chief Wahunsenacawh (Chief Powhatan), was an alliance of roughly 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes in eastern Virginia. Its core territory was in the Tidewater region east of the Fall Line, with influence extending northward to include groups along the Potomac. The Falls Church area lay near the northwestern fringe of the Powhatan Confederacy's sphere of influence3.

The falls of the Potomac River, including the Little Falls, were known to offer abundant fishing opportunities for the tribes. These sites formed a natural barrier for migratory fish, creating prolific fishing spots that Native peoples utilized for millennia4. The falls also acted as a barrier to river navigation and overland transportation, leading to the formation of trails and early settlements5. In 1630, colonist Henry Fleet marveled at the immense catches of sturgeon he saw indigenous people pulling from the Potomac near the falls41.

Local indigenous tribes had rich cultural traditions, with unique customs for marriage, divorce, education, and punishment of wrongdoers. The priests, or kwiocosuk, played a significant role in their society, advising the chiefs on important actions, including war6.

The Anglo-Powhatan Wars (1609-1614, 1622-1632, and 1644-1646) primarily took place further south around Jamestown, but their outcomes affected tribes colony-wide42. The 1646 Treaty of Peace forced the surviving Powhatan tribes to acknowledge English authority and confined them to small tracts of land43. A violent incident in 1675 involving Doeg Indians raiding livestock in northern Virginia led to brutal retaliation by colonists, contributing to Bacon's Rebellion (1676) and further destabilizing remaining native communities in the region7. As European settlers arrived and expanded their settlements, they brought diseases, violence, and cultural disruption8. By approximately 1700, virtually all Indigenous residents had been forced out of the Falls Church vicinity, clearing the way for colonial land grants and settlements44.

Smith, J. & Hole, W. (1624) Virginia. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/99446115/.

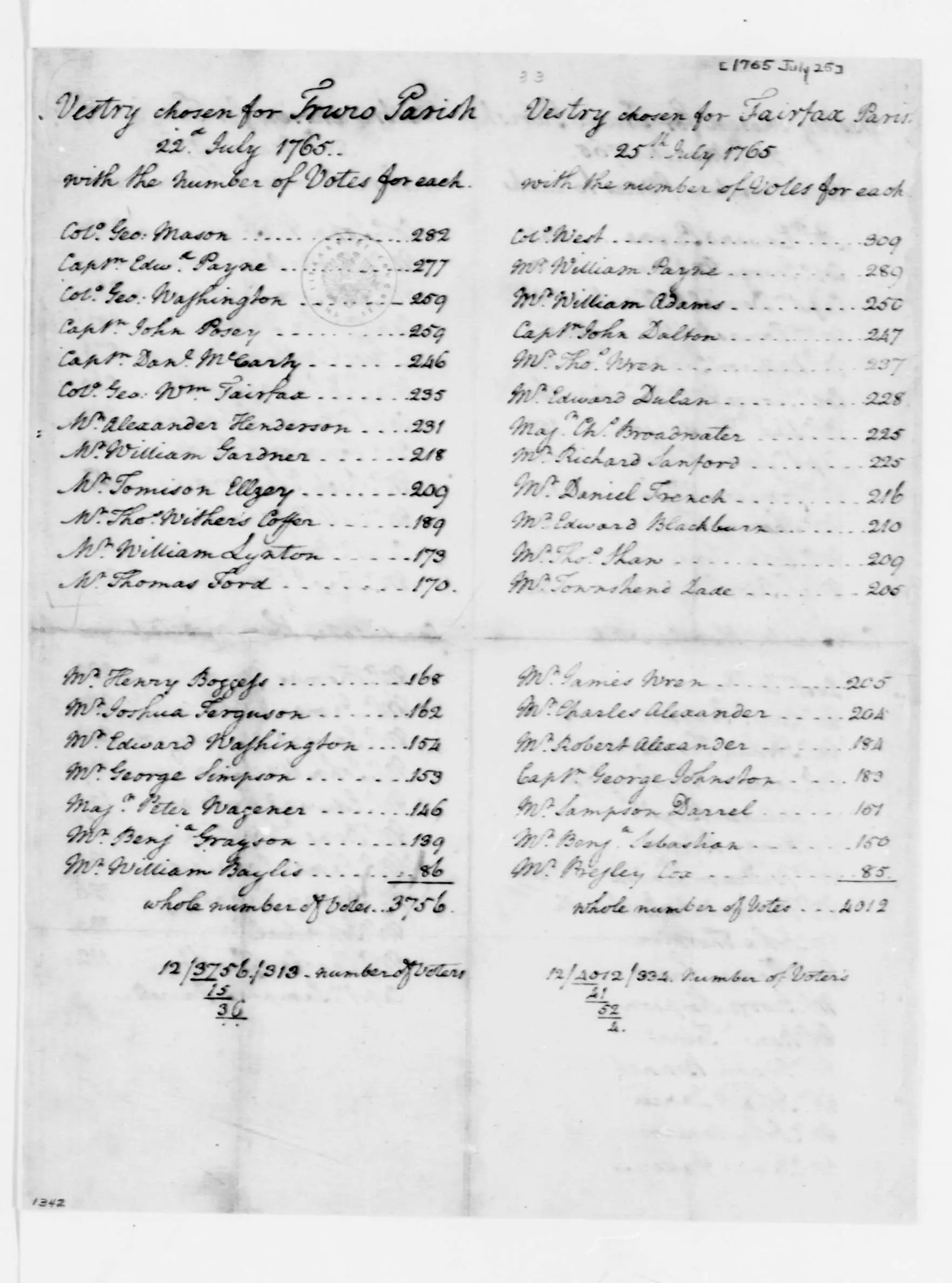

Smith, J. & Hole, W. (1624) Virginia. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/99446115/. (1765) George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Truro Parish and Fairfax Parish, Virginia, Vestry Election Tabulation of Votes. [Manuscript/Mixed Material] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw443132/.

(1765) George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Truro Parish and Fairfax Parish, Virginia, Vestry Election Tabulation of Votes. [Manuscript/Mixed Material] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw443132/. Artist's Rendering of Original Wooden Church. It had a simple rectangular design with a pitched roof. The exterior was made of wooden clapboards, painted white to protect the wood from the elements, and featured a central entrance, flanked by two symmetrical windows fitted with diamond-paned glass, allowing natural light to filter into the interior

Artist's Rendering of Original Wooden Church. It had a simple rectangular design with a pitched roof. The exterior was made of wooden clapboards, painted white to protect the wood from the elements, and featured a central entrance, flanked by two symmetrical windows fitted with diamond-paned glass, allowing natural light to filter into the interior Falls Church, Va. United States Virginia Falls Church, None. [Photographed between 1861 and 1865, printed between 1880 and 1889] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2014645752/.

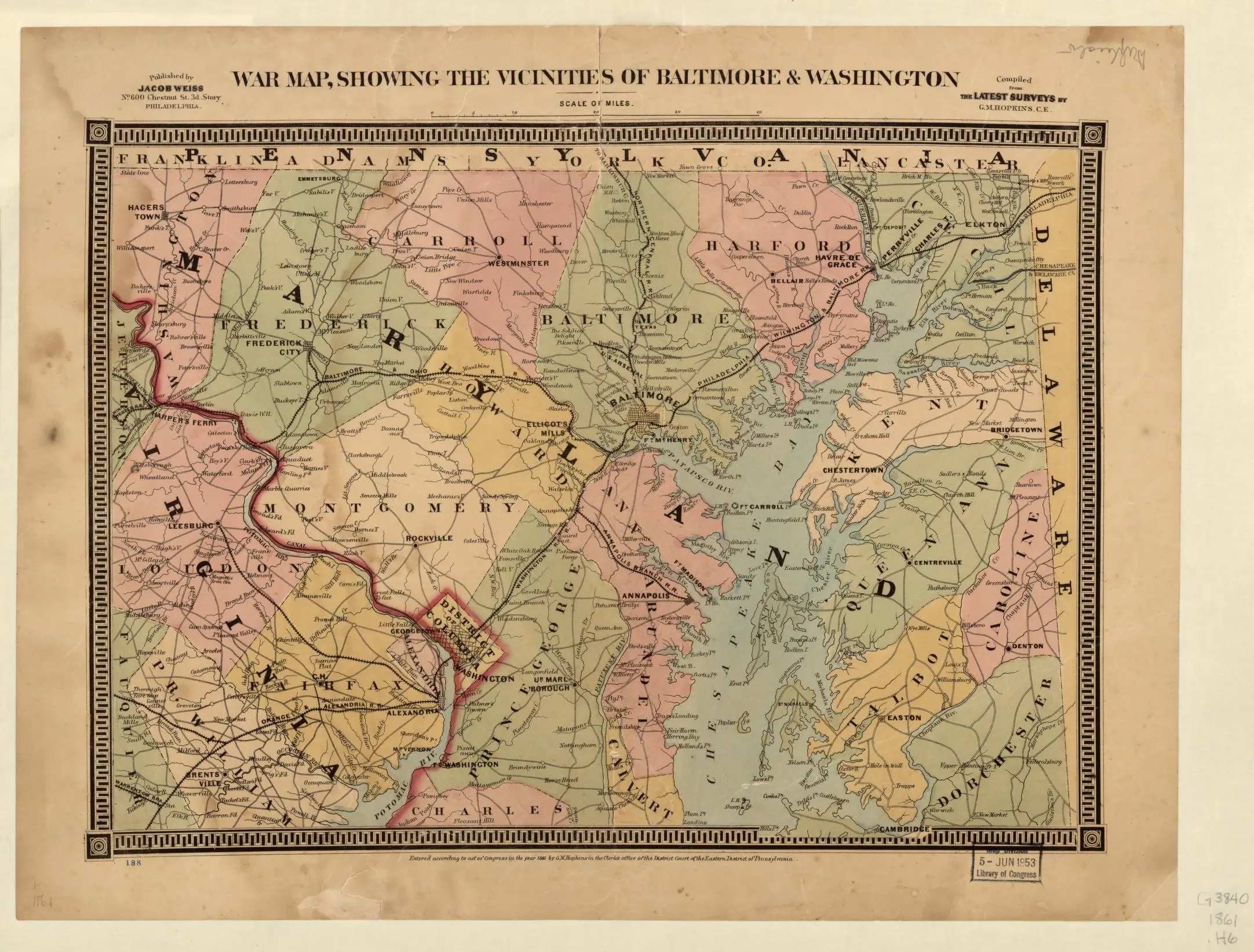

Falls Church, Va. United States Virginia Falls Church, None. [Photographed between 1861 and 1865, printed between 1880 and 1889] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2014645752/. Hopkins, G. M. (1861) War map, showing the vicinities of Baltimore & Washington. Philadelphia, Jacob Weiss. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2009575802/.

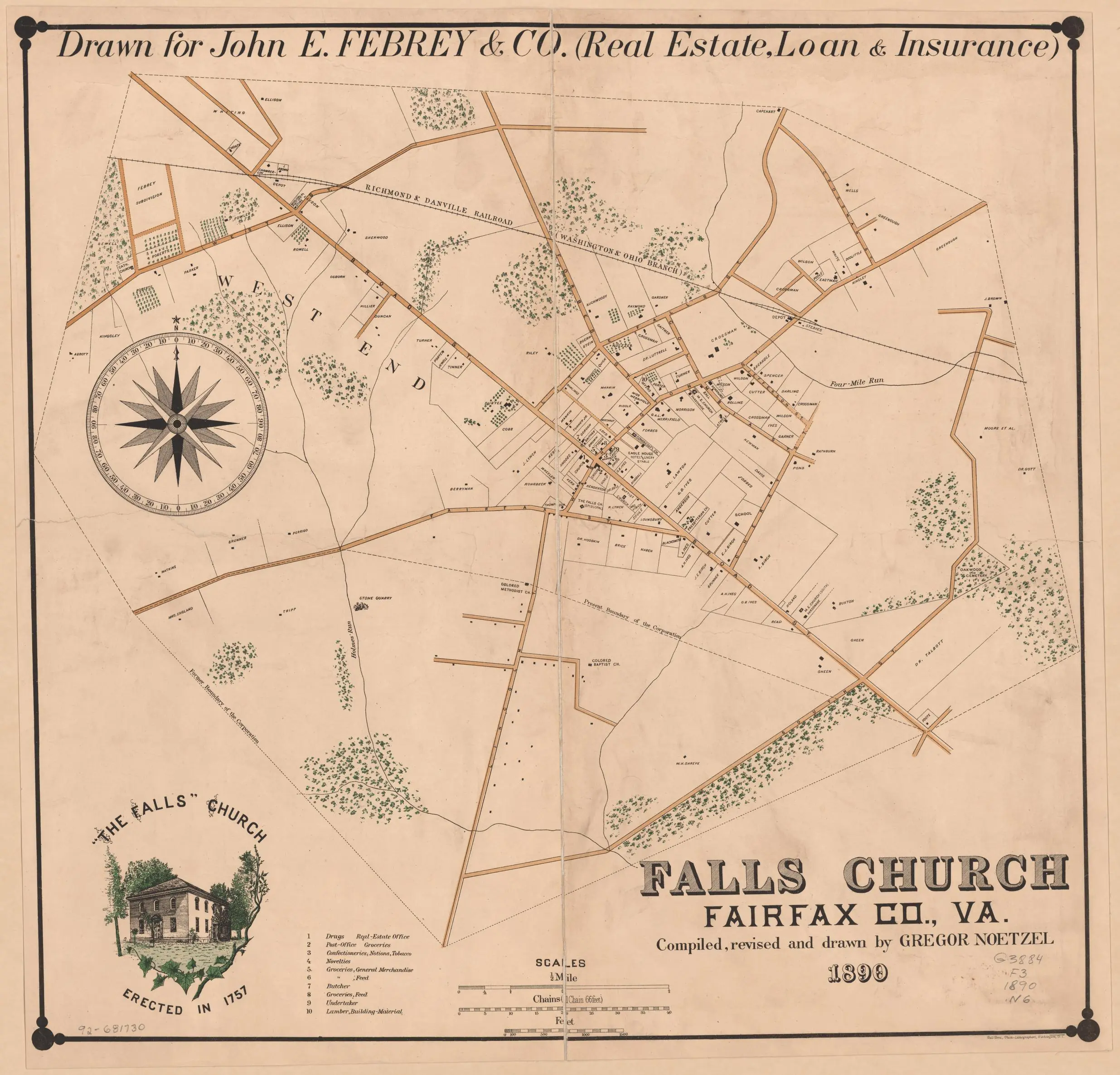

Hopkins, G. M. (1861) War map, showing the vicinities of Baltimore & Washington. Philadelphia, Jacob Weiss. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2009575802/. Noetzel, G. (1890) Falls Church, Fairfax Co., Va. Washington, D.C.: Bell Bros., Photo-Lithographers. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/92681730/.

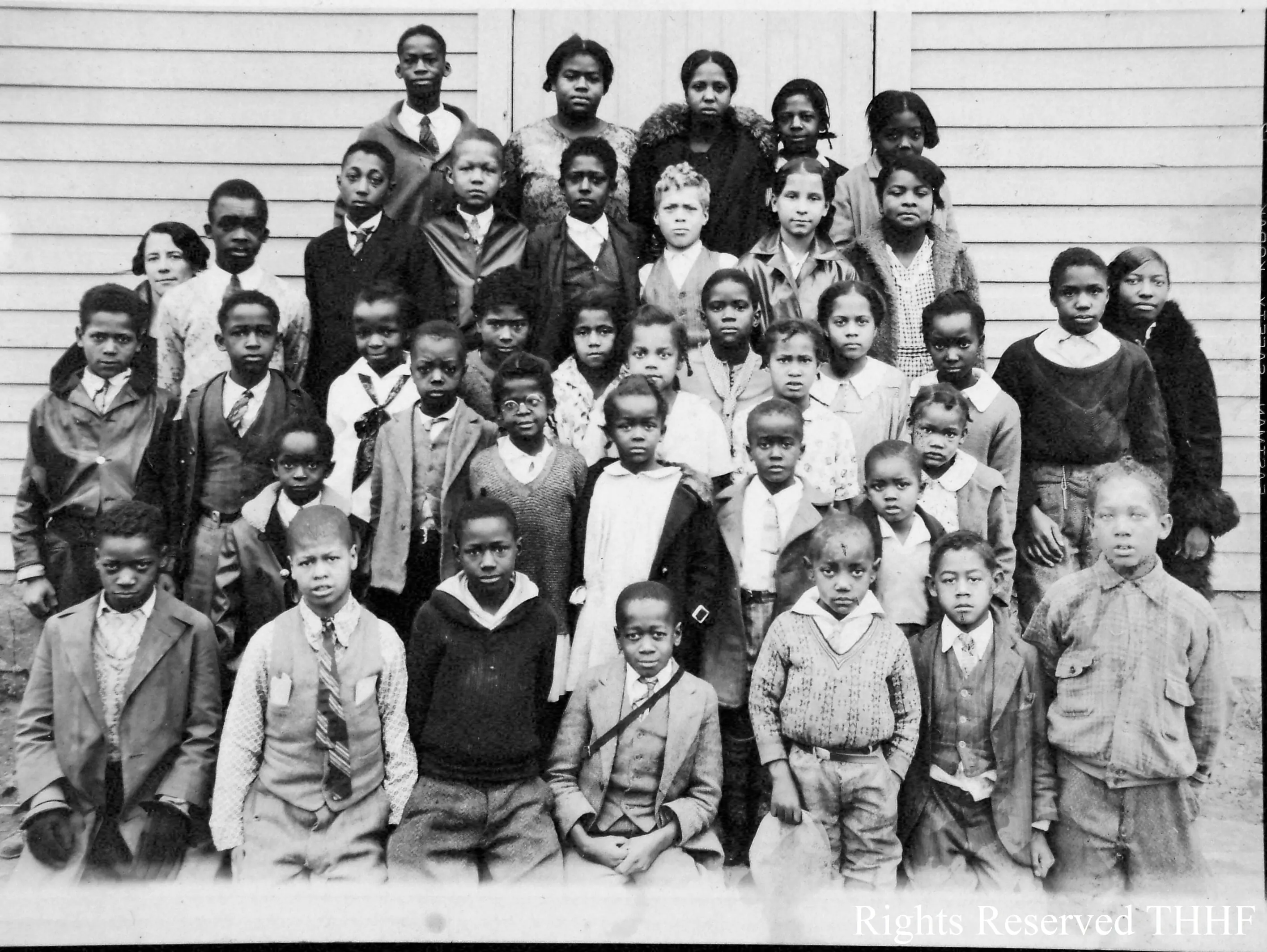

Noetzel, G. (1890) Falls Church, Fairfax Co., Va. Washington, D.C.: Bell Bros., Photo-Lithographers. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/92681730/. Henderson Family Collection, "Mary Ellen Henderson, aka Miss Nellie, and her students in front of the James Lee Colored School," 100 Years Black Falls Church, accessed April 22, 2023, http://100yearsblackfallschurch.org/items/show/25.

Henderson Family Collection, "Mary Ellen Henderson, aka Miss Nellie, and her students in front of the James Lee Colored School," 100 Years Black Falls Church, accessed April 22, 2023, http://100yearsblackfallschurch.org/items/show/25. Historic School Building. Image rights: The City of Falls Church. https://www.fallschurchva.gov/PhotoViewScreen.aspx?PID=8

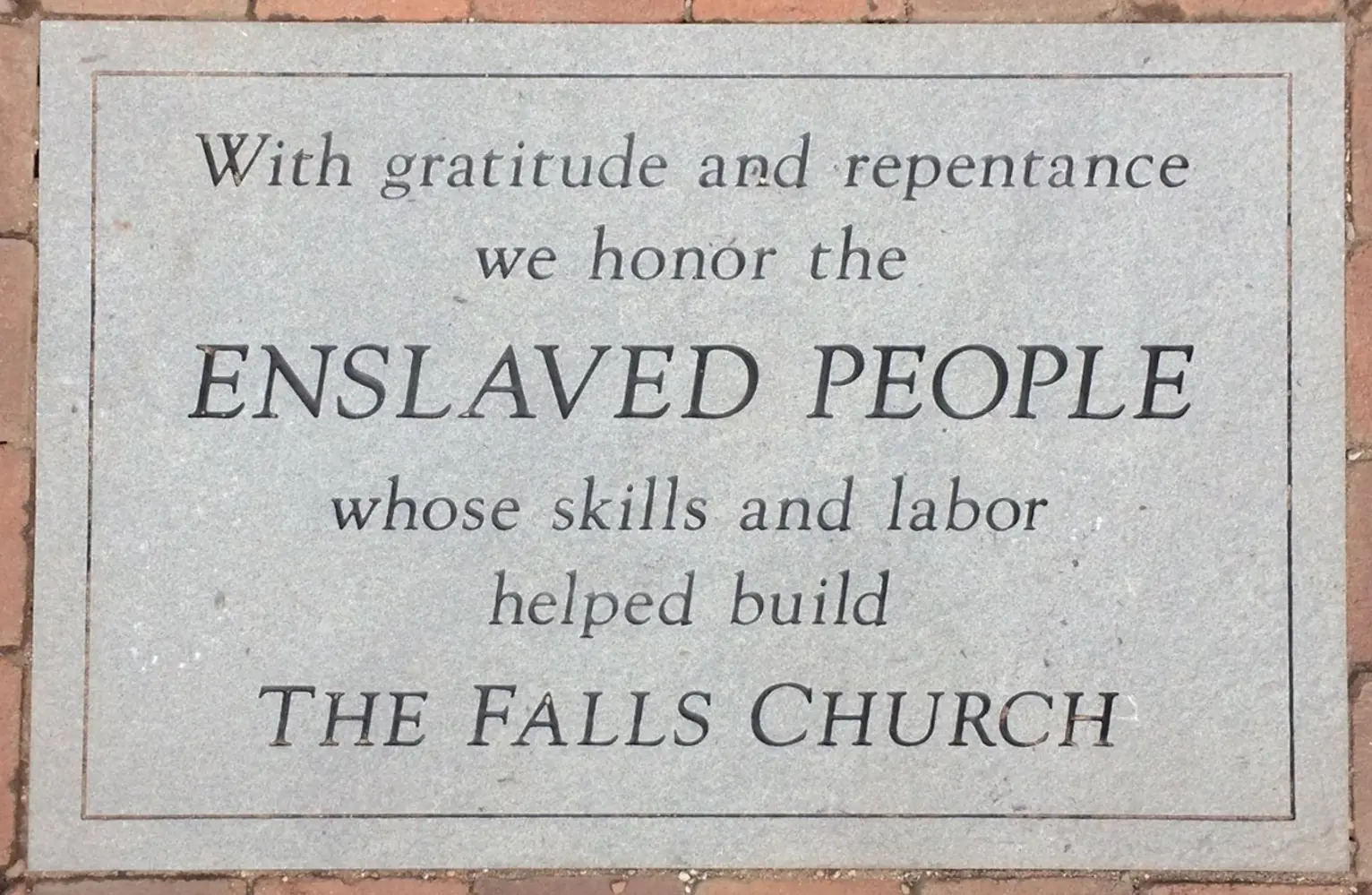

Historic School Building. Image rights: The City of Falls Church. https://www.fallschurchva.gov/PhotoViewScreen.aspx?PID=8 Plaque at The Falls Church dedicated in 2017, acknowledging the contributions of enslaved laborers and offering repentance for the church's role in slavery. Photo: Episcopal News Service.

Plaque at The Falls Church dedicated in 2017, acknowledging the contributions of enslaved laborers and offering repentance for the church's role in slavery. Photo: Episcopal News Service. Little Falls Movement logo representing the Potomac River's Little Falls and the movement's vision of community renewal. Image courtesy of Little Falls Movement.

Little Falls Movement logo representing the Potomac River's Little Falls and the movement's vision of community renewal. Image courtesy of Little Falls Movement.